Limits and possibilities of transnational feminist solidarity:

Analysis of support for Palestine within the civil sector in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia and North Macedonia

The most documented genocide ever is currently underway (1), along with the criminalization of protests and the institutional censorship of support for the Palestinian people. The global movement to end the decades-long occupation of the Palestinian territories as well as the armed and diplomatic support to the Israeli regime, whose militarism has spread to Lebanon and Syria, continues. The destruction of approximately five nuclear bombs, resulting in devastation of the health care system, the orchestrated famine, and the spread of diseases in Gaza have, so far, cause the death of over 127,000 Palestinians (2). Statistics show that in Gaza a child is killed every minute and a woman every 40 minutes and that 902 entire family trees have been wiped off (3) the face of the earth in one year. Although the International Court of Justice, the main judicial body of the UN, is of the opinion that the Palestinians face a "real and imminent risk of genocide", North Macedonia and Serbia, the countries from which we originate, have on various occasions abstained from voting (4) on the UN ceasefire resolution.

As imperialism serves us genocide as a necessary self-defense and any criticism of the Israeli regime as anti-Semitism, politics of forgetting and historical revisionism strengthen. We consider this analysis, initiated during the Feminist Studies organized by the Center for Women's Studies in Belgrade, as a solidarity call to reconsider the limits and possibilities of the civil sector to respond to the growing repression of both the State and its corporate partners, in the hope of finding common alternatives where silence and neutrality are no longer options. Thus, from our collective memory, we highlight, on the one hand, the genocide in Srebrenica and the rape camps in Foča, the war in Kosovo and Metohija, the ethnic cleansing of Macedonians in Aegean Macedonia, Ustasha camps like Jasenovac and the "cleansing" of Yugoslavia from Jews, Roma and Serbs during which Belgrade became the first "Judenfrei" European city in 1942, and on the other hand, the internationalism, and our decolonial and anti-fascist history and struggle. It is precisely these firm beliefs, deeply rooted in the Yugoslav and Balkan territories, that show that liberation calls for fight against racism, militarism, colonialism and totalitarianism, as well as against the production of victimhood. The 80th anniversary of the founding of the mass Anti-Fascist Women's Front of Yugoslavia unequivocally reminds us that liberation and equity are impossible without the voices and resistance of women from all walks of life.

In our post-Yugoslav contexts, civil society developed from anti-war and peace movements, becoming a key infrastructure in the development of the democratic society. The State often withdraws from these processes, making them difficult to decentralize, or directly criminalizes them when it suits the regime's propaganda. With the specifics of each context, war and economic destruction, the struggle with repatriarchalization and predatory privatization of public goods as well as with bureaucratic pressures of imperial and colonial dynamics continues to affect our revolutionary capacities.

In the US, there are many analyses of the abuse - some would say the purpose - of the non-profit industrial complex, primarily in favor of capitalist and state interests. Some of the points raised by the INCITE (5) collective are: monitoring and controlling social justice, redirecting public funds into private hands, redirecting activist energy towards careerism instead of social organizing towards a deeper transformation of society, allowing corporations to mask their exploitative and colonial practices through "charity" work; encouraging social movements to model themselves on capitalist structures rather than question them.

Therefore, an important question arises: How can we trust the current institutions (state, civil and private sector) to respond adequately to the repressive character of the internal and external policies of the countries responsible for the current "collapse of the civilization" if their organizational and program structure, work culture, and bureaucratic overregulation are shaped by the militarized neoliberal capitalism?

In order to address this issue, we conducted a research on the limitations, challenges and possibilities of the civil society and non-profit sector in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia and North Macedonia with a focus on their engagement in relation to the Palestinian issue, primarily the ongoing genocide in Gaza. In this way, we tried to map the role, responses and eventual limitations faced by feminist organizations in the context of growing global and local crises, as well as to look at the role of the civil sector in articulating solidarity and providing support to the Palestinian people.

Research methodology and other reflections

The research encompasses organizations from Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), North Macedonia and Serbia. It consists of two main parts: a questionnaire which was shared on social media and sent to feminist and human rights organizations, and an analysis of their public statements and social media posts.

The questionnaire was filled out by a total of 62 respondents from Bosnia and Herzegovina (22.6%), North Macedonia (30.6%) and Serbia (46.8%), most of whom identified as women (93.6%). Almost half of the respondents (48.4%) are between the ages of 18 and 35, with those over 50 being the fewest (14.5%). Of all respondents, 80.7% were employed in an organization in the period from October 7, 2023 until today. The analysis of online communication and social media includes 33 organizations from Serbia, 28 organizations from North Macedonia, while only 11 organizations were analyzed from BiH. Please keep this information in mind as you continue reading the text.

One of the first questions of our research was meant to explore to what extent respondents were informed about the genocide in Gaza - 85.5% stated that they were regularly informed, and 14.5% occasionally. Respondents are mostly informed through social and independent media (about 80%), while they are least informed through domestic media (about 40%). Among social media platforms, Instagram was mentioned most often (14 times), and from the category of independent media, Novara media and Democracy Now (3 times each). Of the 46 people who stated that they got information through certain activists or groups, 11 of them (17.6%) mentioned human rights defenders, Palestinian journalists and activists, including Francesca Albanese, Motaz Azaiza, and Bisan Owda.

When asked whether this topic activates the interest of public opinion in their country, 43.6% of the sample answered YES, 22.6% answered NO, while the remaining respondents answered indeterminately (‘I don't know’, ‘not enough’, etc.). About half of the respondents from Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina answered affirmatively, while the same percentage from North Macedonia answered NO. Given that the issue of public opinion involves more than the media coverage, we asked "How would you describe the public position of civil society organizations in your country towards this issue?" to which 56.5% of the sample considered that there was no position or that it has not been publicized, which is also the majority opinion of respondents from North Macedonia, while opinions from Serbia and BiH are equally divided between absence of public position and that it is pro-Palestinian/condeming Israel. The core of our research was to assess whether and to what extent civil society organizations have dealt with the issue of genocide in Gaza. In the questionnaire, 45.2% of respondents answered that the organization they work for has made a public announcement regarding this issue, 38.7% said NO, and the remaining respondents said they did not know. Our analysis of public announcements by organizations showed that out of 33 organizations in Serbia, only 4 had announcements on this topic via their communication channels, 4 out of 11 organizations had announced support in BiH, and only 2 out of 28 organizations in North Macedonia. It is worth noting that of these two organizations from North Macedonia, one made a single announcement while the other covered the topic more than 10 times, which we take as a vivid example of what we have observed in all countries - organizations that want to talk about this topic publicly, do so often and with a certain amount of commitment to the subject, while those who do not, do it only symbolically or not at all.

To the question "Do you think that publishing a position on this issue could have negative consequences on the actions of your organization or the civil society globally?", 50% of respondents answered YES, while the second most common answer was ‘I don't know’ (37.1%). Only 12.9% of respondents don’t think there would be negative consequences. The reasoning behind this answer highlights one factor above all others - the impact on the relationship and future cooperation with donors.

Let’s talk about donor politics

Given that we all have experience working in or collaborating with civil society organizations, we predicted the importance of this topic and decided to examine it directly. As many as 88.7% of respondents expressed the opinion that donor policies affect the public stances of civil society, where the majority chose the option ‘it definitely affects’. Special mentions were given to the funds coming from the USA (8 times), the EU (6 times), Germany and the United Kingdom (2 times). The ways in which donor policy most often affects the work of organizations are: bureaucratic overregulation, censorship and self-censorship. One interviewee shared the experience of an organization that had to delete all posts in support of Palestine so that they would not be associated with a donor whose focus is on women's rights. Since then, the organization has not published anything on the subject of Palestine. Neither censorship nor self-censorship as such is easy to spot from the outside, let alone to examine. In an attempt to present that impact in an objective way, we compared the public statements of organizations on the genocide in Gaza with a more "donor-acceptable" war - the war in Ukraine.

Of the 33 analyzed organizations in Serbia, in contrast to 4 that spoke about the genocide in Palestine, 11 spoke about the war in Ukraine. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, among the analyzed organizations, we saw slightly different results, where compared to 3 out of 11 organizations that spoke about Palestine, two spoke about Ukraine. In North Macedonia, compared to 2 out of 28 organizations which covered the topic of Palestine, we saw 7 organizations expressing their views on the war in Ukraine. Seeing the difference in her organization's reporting, one respondent emphasized in her answer the importance of criticizing and condemning the cooperation of domestic authorities and the military industry with Israel and of ending the cooperation with all those who support the genocide, as well as the importance of providing (non)financial support to pro-Palestinian groups in the country.

A qualitative analysis of the texts published by the two analyzed organizations, in which both Ukraine and Palestine were mentioned, showed different linguistic formulations and normalization when talking about these wars. The Russian-Ukrainian conflict has been described as an unexpected Russian attack on Ukraine that turned from a special operation into a multi-year aggression with no end in sight, and the Israeli-Palestinian one as the "traditional" terror of Israel and Hamas, which has been reducing Palestinian living space for decades. These texts condemn the start of the war in Ukraine, as well as the violence against Israeli and Palestinian civilians in the conflict between Hamas and Israel.

Although more organizations dealt with the consequences of the war in Ukraine, that number is still small, given that we primarily included feminist and human rights organizations in our analysis. This brings up the question: Can we safely include donor policies as a major factor in avoiding taking a public stance regarding genocide in Palestine, even when we see evidence that organizations are not being much more vocal about the war in Ukraine?

What are the limiting factors?

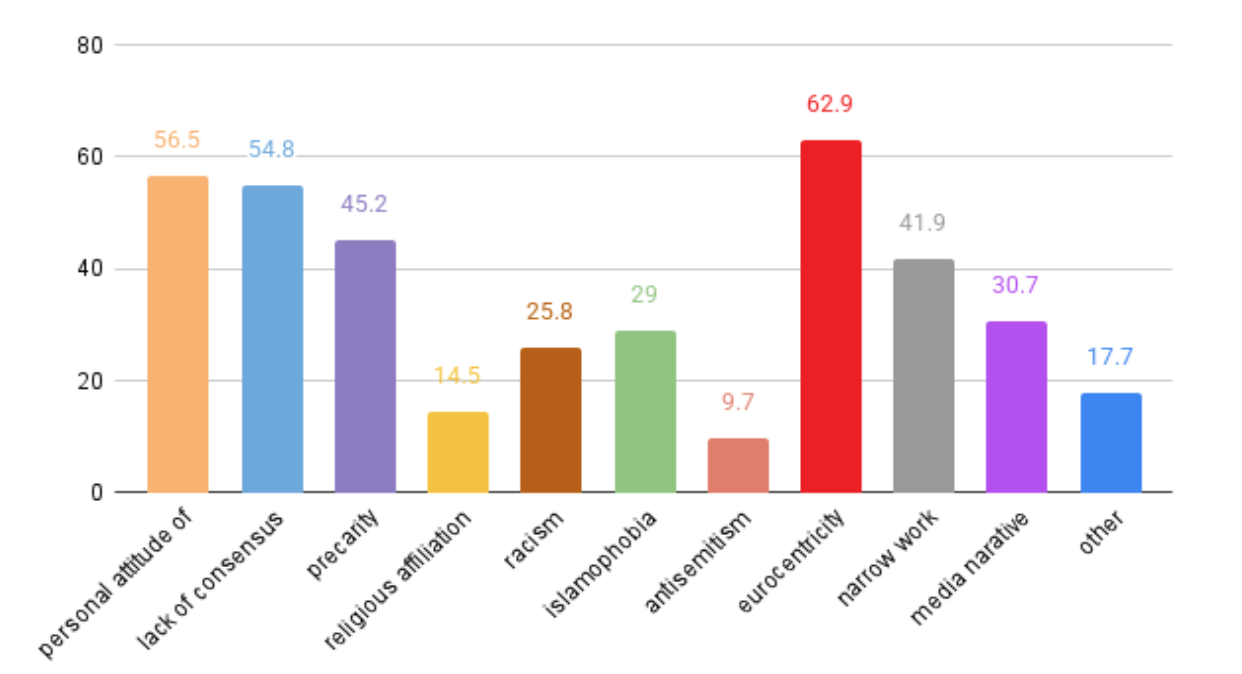

Respondents were given the opportunity to choose one or more answers that they considered to have a significant impact on the public stances of the civil society. Eurocentrism, i.e. "Western-centricity" in the choice of topics they deal with (62.9%) is the most common answer, followed by the personal attitude of individuals within the organization (56.5%) and the lack of consensus in opinion within the organization (54.8%). These responses, in addition to donor policies, also add an individual and social factor. Precarity, as well as narrow specialization in work was chosen by around 40% of respondents, while a quarter identified Islamophobia and racism as important influences on decision-making.

Graph 1. Percentage representation of respondents' answers to the question "Which of the above factors do you recognize as having an important influence on the public stances of the civil society sector in this matter?"

Looking back at the limiting factors, it was important for us to investigate whether the respondents believed that their organization and they individually would have dealt more with the issue of genocide in Gaza if those factors had not existed, with the possibility of a longer explanation. When asked whether the organization would deal with this issue more directly or more frequently, 67.7% answered indecisively (‘maybe’, ‘I don't know’), 19.4% answered affirmatively, and 12.9% answered no. While 46.8% believe that individuals would be more engaged, 33.9% have an undefined position, and 19.4% have said no, among which there are opinions that ‘feminist organizations don’t need to deal with this’. Of the 62 respondents, 30.6% think that, in addition to the existing engagement centering Palestine, additional work is needed both individually and in the organization, 29% think that they are sufficiently engaged individually and as an organization, 19.4% think that they are sufficiently engaged individually, of which 5 respondents do this despite the absence of the organization's public stance.

The analysis of written answers and statistics opens up important questions concerning the tensions between individual and collective positions, work conditions, culture and policies from which the answers derive, as well as the tendency towards the transfer of responsibility that often contains normalizing attitudes. 25.8% of the respondents think that the organization is insufficiently involved, and they themselves do not show interest nor have the need to do something about it, while the attitudes of 33.9% are normalizing, passive and also suggest the transfer of responsibility.

Respondents who emphasized that they expressed their views clearly and without hesitation also feel solidarity and established common values in the workplace, which motivates them to express their political views. Some emphasized the need for financial support for the development of expertise and for engagement of journalists and researchers outside the region. In contrast, 11.3% additionally emphasized the fear of losing jobs and funds, 17.7% the lack of information, solidarity and political education of employees, where two people even quit their jobs in feminist organizations due to the intolerance of hypocrisy on the issue of Gaza, which was followed by precarious and toxic working conditions.

How do we practice transnational feminist solidarity?

Many of the factors mentioned above also affect the possibility of building a strong feminist anti-capitalist front. In all contexts, the most visible forms of resistance came from non-institutional spaces, unconditioned by donor and program policies. Protests, blockades of institutions, but also boycotts of companies (BDS) that financially support human rights violations, pressure on the authorities to stop arming Israel, to recognize the Palestinian state and to have a clear anti-genocide and anti-Zionist stance are among the strategies that respondents mentioned as effective ways of practicing feminist solidarity.

Building long-term autonomous, sustainable and localized movements that "root the struggles in concrete contexts" also requires that decision-making positions, including in the civil society sector, are held by people of integrity who will not allow neither donors nor the State to influence collective values and who will support strategic planning outside of current donor models. This process also entails fighting for the distribution of goods, by moving away from toxic philanthropy, by learning from and joining transfeminist and transnational support networks of the so-called Global South. We can see indications of good and inspiring practices in the work of informal groups, collectives and initiatives that center Palestine in our region, such as the Inicijativa za slobodnu Palestinu (Zagreb), Za slobodnu Palestinu (Belgrade), Site za P4lestina (Skopje), and Feministički antimilitaristički kolektiv (Sarajevo). The current rise of the right worldwide also requires a strategic decolonial strategy and asks us to question our positions, privileges and preferences for white liberal rescue feminism that persistently lures us into the production of the Other.

We need to build horizontal networks of common goods, knowledges and strategies, instead of one-way "aid" and ready-made solutions, through which we "break the imperialist and capitalist structures that enslave our bodies and identities". Radical imagination implies commitment to the struggle for the abolition of corporate militarism, nation-states and their repressive apparatuses. It is not enough to demand a ceasefire and end of genocide if that means staying at the same military-racial-capitalist negotiating table. We owe it to us, to the generations before and after us and to the entire living world, to flip that table by creating spaces of new communions. For that we must really "understand violence" and be open to "radical listening and recognition of the voices of those who are marginalized by colonial structures" as our own and as complicit in the struggles for a dignified life and survival for all.

Footnotes:

(1) We conducted the research and wrote this text during fall and winter of 2024. It was finalized in early January of 2025 during the announcement of the first ceasefire agreement.

(2) Sabar Project: https://www.instagram.com/p/DDex0BcRiMq/?igsh=cGZrY3MydGJkdzZs

(3) Aljazeera, Israeli military wiped out 902 families in Gaza, October 29th, 2024

(4) Северна Македонија гласаше воздржано за резолуцијата на ОН, заедно со дел европски држави, 360степени | 28 октомври, 2023

(5) The Revolution Will Not Be Funded Beyond the Non-Profit Industrial Complex edited by INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence. Publisher: South End Press, 2007. New edition Publisher: Duke University Press, February 2017

(6) What is BDS? https://bdsmovement.net/what-is-bds

(7) Citations in this part are taken from the questionnare responses to the question “How do we practice transnational feminist solidarity?”

Date: January 21st, 2025

About the authors:

Danijela Dedović (2004, Užice) is a feminist, activist and girl from the village who has been engaged in various forms of informal education since the second grade of high school. She studies psychology at the Faculty of Media and Communications and Sociology at the Faculty of Philosophy in Belgrade. She is one of the founders of the association for the empowerment of citizens "OsnaŽene".

Andrijana Papić Mančeva (1986, Skopje) is a translator, supporter of reproductive freedom and part of the team of the Creative Documentary Film Festival "MakeDox". The passion for living with less waste, which has been growing with parenthood for a decade, has turned into an inexhaustible interest in ecofeminism through the prism of intersectionality.

Nataša Prljević (1986, Užice) is an artist, culture worker and organizer. Through collaborative and collective practices, she deals with the role of art in social changes and strengthening of transnational feminist solidarity. She is a co-founder of the HEKLER platform and collective that fosters critical and experimental examination of hospitality and conflict, and a member of the initiative Four Waters Meeting Point.

Hristina Tonić (1999, Niš) is a youth activist who deals with feminist and other political issues through the prism of intersectionality, with diverse volunteer experience. She is a final year psychology student at the Faculty of Philosophy in Niš and wants to build her expertise at the intersection of psychology, politics and activism.